“The

Tullos Toughs”

By

Richard Thornton Fox

Prior

to discovery of petroleum in the locality, the only other industry was

harvesting timber. Vast stands of virgin growth longleaf pine was extant in the

1920s. Large sawmill towns, e.g., Selma, Rochelle, and Urania were built by

lumber companies to attract and provide a stable work force.

Nearly

all houses in the towns were owned by the company, as was a single mercantile

store. The caliber of employee housing depended on the status of the worker.

Supervisors lived comfortably, but common laborers did not fare nearly so well.

Nominal rent was withheld from employees' wages each payday. All workers were

expected to use the company store for all their needs. Sometimes workers were

paid in "script" instead of cash. Script had a value somewhat more

than cash at the company store, but could only be used at this place. Credit was

available from the store but was at high interest.

Should

any employee be noted to buy too many of his necessities at stores out of town,

he was nearly certain to be warned against this practice. Warnings were taken

seriously since loss of a job risked placing the family into immediate poverty.

Other than hard scrabble share cropping, there was no other employment

available. If all these practices sound like a feudal system of worker

exploitation, this is exactly what it was. Given these managerial techniques, it

is not surprising two of the towns mentioned, Rochelle and Selma, were

relatively short lived When the available stand of timber was cut, that was it.

The mills shut down and the people just faded away. The timber company that

operated in Urania was more far sighted and early on started a reforestation

program to replace trees harvested. Their

operations still continue in Urania.

The

disposal problem was simple to solve in those non-enlightened times. The brine

was simply directed to the nearest ditch and allowed to run to a lower level. It

always ended up in a swamp or creek. The salt content of this brine was several

times more concentrated than sea water and invariably contained some suspended

petroleum. The end result was the brine contaminated and killed all vegetation

in its path and wreaked havoc on wetlands and waterways. Though such practices

are not longer allowed, the environmental scars are still visible.

Working

in the oil fields was hard, dirty and physically demanding work. Conditions were

compounded by the climate of central Louisiana where summer temperatures

routinely are more than 100 F. and torrential rains and tornados are common.

Predictably, the men who did the work reflected their surroundings. They were

generally tough, honest, direct and occasionally violent. Morals, politics and

religion were observed from one extreme or another. There was little middle

ground or room for compromise on most issues. Arguments often led to physical

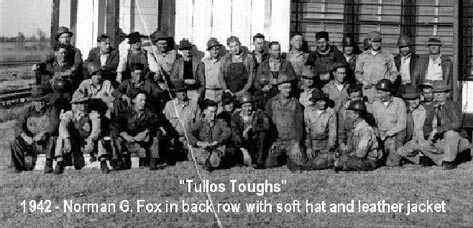

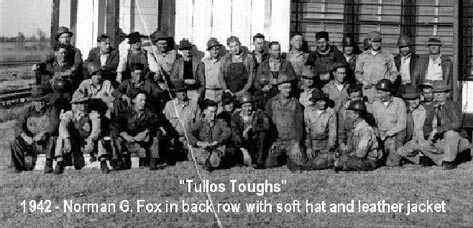

confrontations, sometime with tragic results. Sometimes people from surrounding

communities would refer to the local inhabitants as the “Tullos Toughs."

The

earth in Tullos was a peculiar type of clay known locally as "gumbo."

When it rained, which was a frequent occurrence, the gumbo melted into a mud

that stuck to the feet with tenacity. After walking a few yards in this goo each

foot became the size of a dinner plate. The color of the gumbo ranged from black

to red. It permeated the entire area, houses, churches, stores, everything.

Actually, outsiders referred to the town as "Mudville." With good

reason.

This

then is where Norman and Ruby would live the greater part of their lives. Norman

seemed suited to fit in the general atmosphere. He recalled to me when he first

came to town he saw a person mistreating a mule. So he, Norman, picked up a

piece of 2x4 lumber and "knocked the offender in the head." The

mistreatment stopped.

Norman

came to Tullos as the district superintendent for the oil company. The company

was operating about 50 producing wells, all within a radius of S miles. About 40

full time employees were in the local organization. Under the direct control of

the superintendent were a general foreman, a warehouse supervisor, and an

accountant/shipping agent who kept track of and oversaw shipment of petroleum

produced. The superintendent and his principal assistants each lived in a

"company house" built and maintained by the company.

Each

of these houses had less than 1000 square feet living space, but they did have

gas heat, running water and inside plumbing. No matter the gas had little odor

and was dangerous to live with, the running water was really not potable

(everyone had a tank or rain barrel to collect drinking water). Plumbing was

piped to a convenient ditch. Indoor plumbing and running water were marks of

distinction in the early days of this town. The only other company house was a

small cottage occupied by a warehouse assistant a black man named George

Johnson, and his wife Polly. The cottage was located near the warehouse which

provided day to day storage of supplies, pipe, fittings and working equipment.

George had encyclopedic knowledge of what was on hand and where it was located

This was no mean feat and he was recognized as an indispensable part of the

organization.

The

main work force consisted of small groups of men called "gangs"; who

were led by a man titled, appropriately, "gang pusher." Usually there

six or seven men in a gang. Individual workers were known as

"roustabouts." Gangs did the laborious work of maintaining the wells

is a producing condition required pulling up and dismantling hundreds of feet of

pipe tubing to find and repair a defective section. There was no way of doing

this without becoming covered from head to toe by oil, water and mud. Doing this

in the July and August climate of Louisiana could cause even the heartiest to

"faint and fall out." But, no one ever quit or walked off. Jobs were

too precious. Hopefully the wells pumped night and day to maximize production.

Some men known as "pumpers" worked in individual 8 hour shifts to

visit a number of wells on a set schedule throughout the day to ensure all was

in order. At night this was a lonely and sometimes dangerous job. Many carried a

gun "just in case."

Besides

the Arkansas Fuel Oil Company, the other production company in town was the H.

L. Hunt organization, know as the Placid Oil Company. Placid was approximately

the same size as the Arkansas Fuel Oil Company.

There were a few "poor boy" outfits operating three or four

wells each, but their production was always much less than that or the larger

companies.

Besides

the Arkansas Fuel Oil Company, the other production company in town was the H.

L. Hunt organization, know as the Placid Oil Company. Placid was approximately

the same size as the Arkansas Fuel Oil Company.

There were a few "poor boy" outfits operating three or four

wells each, but their production was always much less than that or the larger

companies.

During

the early boom days life in Tullos was lively. The main was dirt, or mud if it

rained. One shooting incident occurred to which a witness testified "it was

so could not see across the street." The prosecution allowed that in fact

the mud in the street was so bad on that day a mule team got stuck right in the

middle. Subornation of witnesses is not a recent thing. Law enforcement in the

town was accomplished by a town marshal who had an office in a one room jail

with two cells. Most local problems were caused by drinking and/or fighting. The

marshal had to be a man of great physical courage and could never yield to a

threat, as many troublemakers found out the hard way. The marshal was paid

poorly, not universally admired, but nearly always obeyed.

By

the mid 1930s the boom was over and the companies worked to maintain production

already established. The town stabilized into a village of two small grocery

stores, a drugstore, a hardware store, 2 dry goods stores, a picture show

(movie), doctor's office and 2 filling stations. All of these businesses , with

the exception of one filling station, were mom-and-pop operations. These were

two churches, one reasonable large Baptist Church, and one smaller Methodist

Church. On occasion Pentecostal tent revivals would be held where believers

would speak in tongues. There was no doubting the sincerity of the believers and

large crowds attended.

The

town school conducted grades 1 - 9. Classes were always small and one teacher

taught all subjects for the year group in the lower grades. There was no public

transportation to the school since nearly all of the children lived nearby.

Students either brought a lunch or went home for the noon meal. There were no

discipline problems of consequence. Bad behavior was not tolerated by the

teacher, principal, or parents. No doubt the system was authoritative - neither

was there any doubt it was effective in providing a basic education.

There

was little change in the town after the boom until the end of the 1930s when the

war started in Europe and it was obvious the United States would be drawn in.

The draft started and the young men left for the armed forces. Every able bodied

single man between 18 and 26 was called. Later,

married men were inducted. Exceptions from the draft were nearly unheard of.

Even if a man had a valid reason not to serve, he was generally considered to b

a slacker and looked down on.

The

approaching war fueled an increased requirement for petroleum and new wells were

drilled in the existing fields. The company headquarters in Shreveport,

Louisiana, sent geologists and engineers to Tullos to survey Likely locations

and determine where the new holes were be drilled After due consultation between

all concerned, a wooden take was placed in the ground to show the exact site for

the new well. When the search team had left the area, Norman would invariable

pull up the stake and move it a foot or two to one side "just for good

luck." This strategy must have worked for it was rare to come up with a dry

hole or non-productive well.

Norman

ran a tight ship and was extraordinarily well thought of by the company. He knew

his job and was satisfied with his position in the organization. He was called

"N. G." by his friends. Employees addressed him as "Boss" or

"Cap'n Fox" in person, but referred to him as `The Kingfish"

among themselves. Norman was an accomplished angler and was reputed to "be

able to catch fish out of a mud hole.."

Evidence

of the war being fought so far away was clear enough. Army camps Beauregard,

Claiborne and Livingston were about fifty miles away and basic training was

conducted throughout the area for hundreds of thousands of inductees. Trucks and

tanks traveled through the area single and in convoys throughout the day and

night. It seemed most of the soldiers wee from the northern states and they did

not appreciate the climate, red bugs, ticks and snakes the locals had to contend

with. Whenever possible people in the town would invite soldiers on maneuvers or

otherwise passing through in for meals. These occasions were enjoyed by all

concerned and a lot was learned from guests and hosts.

Parents

hoped someone else was likewise extending hospitality to their son away in

service. Locally, the civilian

population was subject to the same restrictions as the rest of the country.

Shoes, sugar, coffee, cigarettes, tires and gasoline were rationed. None

of these restrictions caused any hardship, and only occasional minor

inconvenience. Though details of

the actual conflict were somewhat obscured by censorship and lack of real time

media coverage, people knew how well off they were to be out of harms way. Early

on a local Civil Defense Corps was established to provide some defense against a

bombing attack. No doubt this came about because of the havoc being caused in

England by the Nazis. In retrospect it is hard to see why or how a bombing

attack would be carried out against Tullos, but the drills did keep the war in

focus.

The

occasional report of a local man being killed or wounded in action also served

to bring the war close. Norman and

Ruby's son Raymond had started to college at the Louisiana Polytechnic Institute

in Ruston, La., in the fall of 1941. He was 16 at the time (Louisiana high

schools finished at grade 11 ). Before

he was 18, Raymond enlisted in the Navy but was not called to active service

until 1943. He served as an aircraft radar technician in PBY Catalina flying

boats and on aircraft tenders. He was on one of the ships in Tokyo Bay when the

Japanese surrendered in 1945. Richard, Norman and Ruby's youngest son, enlisted

in the Navy in September 1945.

In

1946 Ruby was diagnosed as having breast cancer and underwent a radical

mastectomy. The operation was not completely successful. The cancer metastasized

and she died of further complications in 1947. She is buried in the Thornton

family cemetery in Liberty, Texas. Norman

continued living in the company house after Ruby's death. In 1949 he married

again, but the union was not happy

and was being dissolved when Norman had a stroke in late 1950. The illness left

him permanently disabled with the loss of use of his left arm and impaired

walking ability. After an initial stay at a hospital in Shreveport, he stayed a

period at the Veteran's Hospital there until he went to live with his son

Raymond, then in Natchez, Mississippi.

In

recognition of the exceptional service Norman had given, the Cities Service Oil

Company continued Norman on full salary from the time of his stroke until he

reached normal retirement age in 1956, and then kept him on retirement pay. This

made him independent in so far as financial needs were concerned, and it gave

him great comfort to be able to pay for his own expenses for the rest of his

life.

Raymond and his family did all in their power to provide for Norman, but his strong sense of independence led him to seek other alternatives. Raymond was employed by Lane Wells, a oil and gas drilling company and it was necessary for him to relocate every two years so as dictated by the circumstances of the business. Richard was a newly commissioned officer in the Navy and on sea duty. Norman always had good relationships with his mother-in-law, Carrie Thornton, in Liberty, Texas. He stayed with her for some time prior to her death in 1960. About then, Raymond was transferred to Lake Charles, La., and Norman moved to a nursing home there to be close to him, but still have, in effect, his own place to stay. Raymond was killed in a firearms accident in 1962 in New Iberia, La., where he was then living. Norman remained in Lake Charles until he died on 28 December 1963 following three weeks in a hospital. Death was caused by a new cerebral thrombosis (stroke) brought on in part by pneumonia. Norman is buried in Liberty, Texas, alongside Ruby.

|

Compiled by

Richard N. Fox |

|

|

Web design by Richard Fox |

|